Request Appointment

Enter your details and we will be in touch with you shortly;

Or call

8655885566

between 8 am and 8 pm.

Kriti Khanna1 · Shikha Jain · Gautam Shetty · Nishtha Rahlan1 · C. S. Ram

Spine pain is considered a biopsychosocial illness where physical, behavioural, occupational, and socioeconomic factors play an important role in causation and outcomes after treatment [1, 2]. Considering that most cases of spine pain are secondary to “non-specifc” causes, associated psychosocial factors need to be identifed and addressed to make treatment more efective [3]. Hence, current clinical guidelines recommend that psychosocial risk factors should be identifed and addressed in patients seeking conservative management of their spine pain [1, 4].

Psychosocial factors such as distress/anxiety, fear-avoidance beliefs (FAB), kinesiophobia, low morale, social withdrawal, expectation of passive treatment, catastrophizing, and poor work environment are known to be risk factors for the development of chronicity in low back pain (LBP) [5]. Furthermore, these psychosocial factors can afect patients’ response to treatment and can act as barriers to recovery in primary care [6]. Similar to high-income communities, patients with LBP in low- and middle-income communities, may also have higher levels of psychosocial risk factors such as anxiety, depression, and somatisation along with an increased socioeconomic burden [1, 7]. However, lack of awareness, non-identifcation of these factors, and exclusion of the psychological aspect from treatment both by patients and their healthcare providers may lead to poor treatment outcome, chronicity of LBP, and persistence of disability in such communities.

The literature is lacking on the burden of psychological risk factors among patients seeking treatment for their spine pain in a developing country like India. Previous crosssectional studies conducted on specifc populations such as students and professionals have reported increased stress levels, and social burden among subjects with LBP [8, 9]. However few studies involving Indian subjects have used standard instruments such as the Fear-avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) [10], the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) [11], and the STarT Back Tool (SBT) [12], to quantify the burden of specifc psychological factors in such subjects.

Knowing the psychological profle of Indian patients seeking treatment for their spine pain in terms of FAB, kinesiophobia, and risk of persistent disability will help identify patients at risk for poor treatment outcome and chronicity and modify these factors early during treatment to ensure good outcomes. Hence the aim of this study was to determine the burden of FAB, kinesiophobia, and risk of persistent disability among Indians with spine pain. We hypothesised that a majority of such patients will have poor or high-risk FAB, and kinesiophobia, persistent disability scores which will correlate to their pain and disability at presentation.

This prospective cohort study was conducted at an outpatient clinic specializing in spine rehabilitation (QI Spine Clinic, Dwarka, New Delhi, India) over a 3-month period from January 2020 to March 2020. Subjects who visited the outpatient clinic for assessment and physical rehabilitation treatment of their spine pain were eligible for participation in this study. The study protocol was approved by an institutional review board and ethics committee. All participants signed informed consent for participation in this study and the use of their anonymized data for research.

Study subjects were recruited from patients who came for evaluation and treatment of their spine pain at our spine rehabilitation outpatient clinic. The inclusion criterion was patients who presented at the clinic for evaluation and treatment of their mechanical spine pain. The exclusion criteria were patients with peripheral joints involvement (hip, knee, and ankle joints), patients with structural kyphotic or scoliotic deformities, patients with peripheral neuropathy, patients who have undergone spine surgery and patients with incomplete clinical records.

All subjects underwent clinical evaluation which included proper history and a thorough clinical examination during the frst consultation. All subjects were examined for posture, spine range of movement, straight leg raising (SLR) test, and motor and sensory function. Based on clinical history, presentation, and examination fndings, subjects with spine pain were diagnosed with mechanical spine pain if the pain arose from the spine, intervertebral discs, or surrounding soft tissues and worsened with specifc spine movement and improved with rest. Pain intensity was measured in all patients using the numerical pain rating scale (NPRS) score [13], and disability using the Oswestry disability index (ODI) or neck disability index (NDI) [14, 15].

All subjects were administered the Fear-avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) [10], the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) [11], and the Keele STarT Back Screening Tool (SBT) [12], at the time of registration and before clinical evaluation. The Fear-avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) was a 16-item questionnaire that measured fearavoidance beliefs and expectations [10]. It consisted of two subscales—a 7-item work subscale (FAB-W, range 0–42), and a 4-item physical activity subscale (FAB-P, range 0–24) with each item on the two subscales scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale (ranging from completely agree to completely disagree) [10]. A higher FAB score indicated higher fear-avoidance beliefs in the patient and a FAB-W score of≥25 [16], and a FAB-P score of≥15 was considered high [17]. The Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) was a 17-item scale that measured kinesiophobia [11]. All items were scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale (ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree) [11]. A higher TSK score indicated a higher risk of kinesiophobia in the patient and a TSK score of>37 was considered medium to high-risk [17]. The Keele STarT Back Screening Tool (SBT) consisted of a 9-item tool that estimated the risk of persistent disabling symptoms [12]. Patients with an SBT total score≥4 were interpreted as belonging to the medium to high-risk group with poorer prognosis and those with an SBT total score<4 were in the low-risk group [18].

Demographic data including gender, age, body mass index (BMI), and lifestyle (sedentary, semi-active, or active), and duration of symptoms (acute/subacute ≤ 12 weeks, chronic > 12 weeks) were collected and analyzed in all participants. Psychological variables of Fear-avoidance Beliefs work (FAB-W) and physical activity (FAB-P) scores, the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK) score, and the STarT Back Tool (SBT) score were collected from all patients at the time of consultation.

Categorical data were compared using the Fisher’s test or Chi-square test, and continuous data were compared using t test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). For subgroup analysis, the FAB-W, FAB-P, TSK, and SBT scores were compared among two subgroups based on pain duration (acute/subacute and chronic), three subgroups based on NPRS score (≤3, 4–7, and>7), and 2 subgroups based on disability categories (moderate or minimal and bed-ridden, crippled or severe). A multivariate analysis was performed to determine the efect of NPRS and ODI/NDI scores, age, gender, BMI, lifestyle, pain duration, and pain location (lower back or neck and/or upper back) on FAB-W, FAB-P, TSK, and SBT scores. A p value of<0.05 was considered signifcant. Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad QuickCalcs online statistical analysis tool (GraphPad Software, San Diego USA).

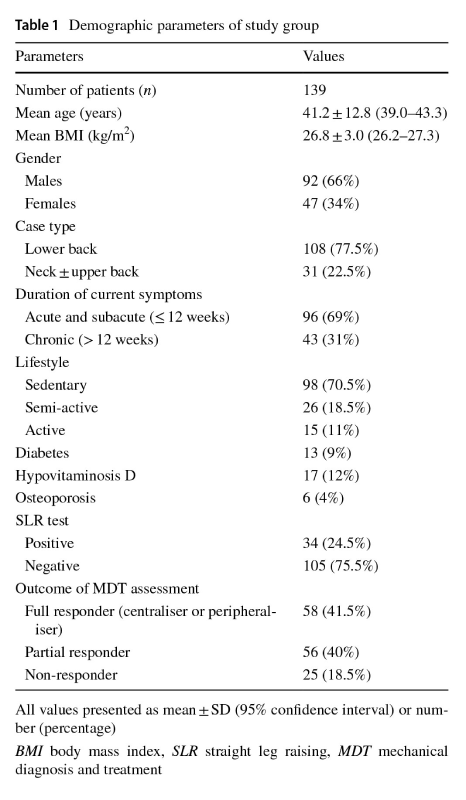

A total of 145 patients with spine pain were eligible for participation in the study. Based on exclusion criteria, 6 patients were excluded (2 patients with peripheral joint involvement, 1 patient who have undergone spine surgery, and 3 patients with incomplete clinical records), and 139 patients were analyzed for the study. The demographic details and clinical presentation of the study population are summarised in Table 1. A majority of the patients were males (66%), had lower back pain (77.5%), had acute or subacute spine pain (69%), and had a sedentary lifestyle (70.5%). The clinical and psychological details of the study population are summarised in Table 2. A majority of the patients had an NPRS score between 4 and 7 (67%) and had a moderate disability (48%).

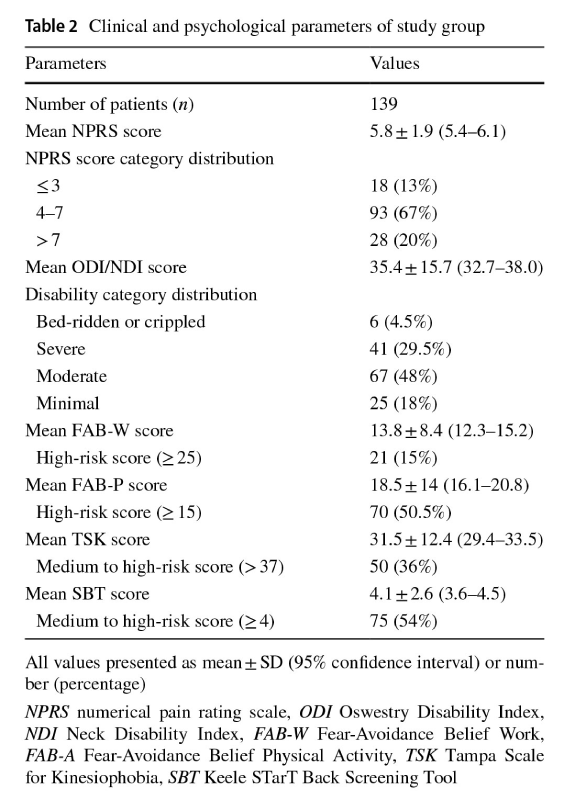

The mean FAB-W score was 13.8±8.4 with 15% of patients having a high-risk FAB score, and the mean FAB-P score was 18.5±14 with 50.5% of patients had a high-risk FAB-P score (Table 2). The mean TSK score was 31.5±12.4 with 36% of patients having a medium to high-risk TSK score (Table 2). The mean SBT score was 4.1±2.6 and a majority of the patients had a medium to high-risk SBT score (54%) (Table 2).

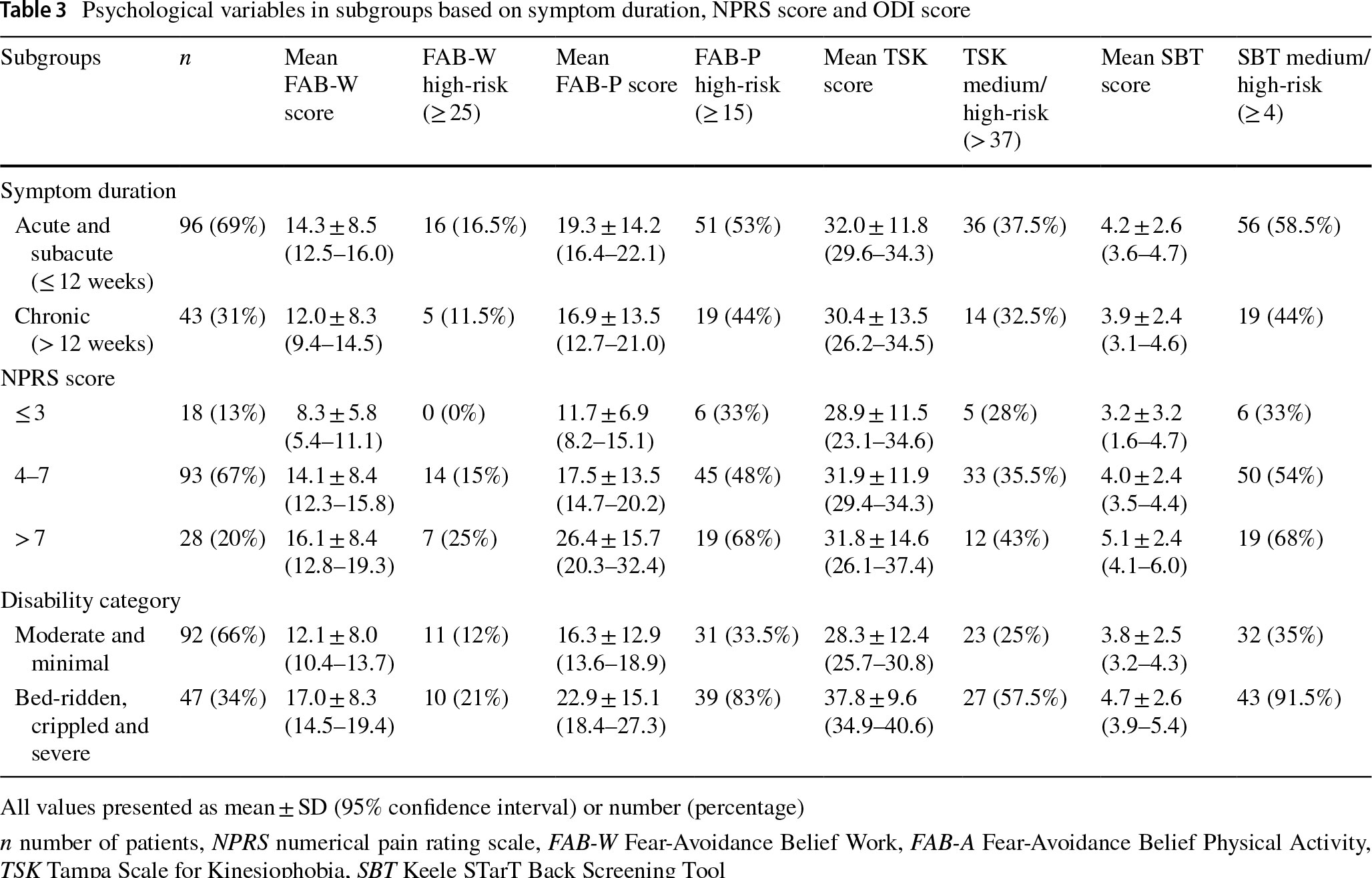

The mean FAB-W score was signifcantly higher in patients with NPRS score>7 (p=0.001) and in patients with severe, crippled or bed-ridden disability (p=0.001) but was not signifcantly diferent in patients with acute/subacute when compared to chronic spine pain (p=0.13) (Table 3). The percentage of patients with high-risk FAB-W score was signifcantly higher in patients with NPRS score>7 (p=0.03) but was not signifcantly diferent in disability (p=0.20) and acute/chronic (p=0.60) subgroups (Table 3). The mean FAB-P score was significantly higher in patients with NPRS score>7 (p=0.001) and in patients with severe, crippled or bed-ridden disability (p=0.001) but was not signifcantly diferent in patients with acute/ subacute when compared to chronic spine pain (p=0.13) (Table 3). The percentage of patients with high-risk FAB-P score was significantly higher in patients with NPRS score>7 (p=0.03) and in patients with severe, crippled or bed-ridden disability (p<0.0001) but was not signifcantly diferent in patients with acute/subacute when compared to chronic spine pain (p=0.36) (Table 3).

The mean TSK score was signifcantly higher in patients with severe, crippled or bed-ridden disability (p<0.0001) but was not signifcantly diferent in patients with NPRS score>7 when compared to patients with NPRS score≤3 (p=0.48), and was not signifcantly diferent in patients with acute/subacute when compared to chronic spine pain (p=0.48) (Table 3). The percentage of patients with medium or high-risk TSK score was signifcantly higher in patients with severe, crippled or bed-ridden disability (p=0.0003) but was not signifcantly diferent in patients with NPRS score>7 when compared to patients with NPRS score≤3 (p=0.36), and in patients with acute/subacute when compared to chronic spine pain (p=0.70) (Table 3).

The mean SBT score was signifcantly higher in patients with NPRS score>7 (p=0.02) and in patients with severe, crippled or bed-ridden disability (p=0.04) but was not signifcantly diferent in patients with acute/subacute when compared to chronic spine pain (p=0.54) (Table 3). The percentage of patients with medium or high-risk SBT score was signifcantly higher in patients with NPRS score>7 (p=0.03) and in patients with severe, crippled or bed-ridden disability (p<0.0001) but was not signifcantly diferent in patients with acute/subacute when compared to chronic spine pain (p=0.14) (Table 3).

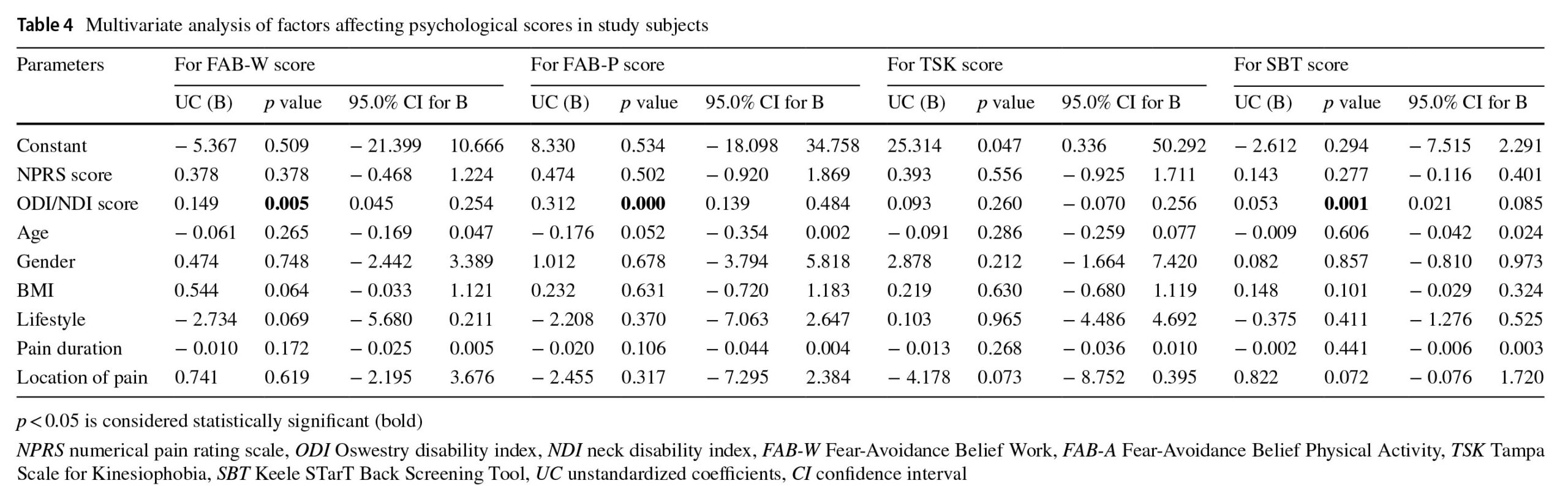

A higher ODI/NDI score was signifcantly associated with higher FAB-W, FAB-P, and SBT scores whereas age, gender, BMI, lifestyle, pain duration, and pain location showed no signifcant association (Table 4). No factor was signifcantly associated with TSK score (Table 4).

The main fndings of our study were: (1) a majority of patients had medium to high-risk FAB-P and SBT scores and low risk FAB-W and TSK scores; (2) the mean FAB-W, FAB-P, and SBT scores were signifcantly higher in patients with NPRS score>7 and in patients with severe, crippled or bed-ridden disability; and (3) ODI or NDI score was a signifcant predictor for FAB-W, FAB-P, and SBT scores.

A majority of Indian patients seeking rehabilitation treatment for their spine pain had high-risk FAB-P score (50.5%) related to physical activity but only 15% of patients had a high-risk FAB-W score related to their work. This fnding was confrmed by a previous cross-sectional study on FAB among 227 women with chronic LBP, which reported 25.5% patients with high-risk FAB-P score and 6% patients with high-risk FAB-W score [19]. However, this was in contrast to the fndings of another recent study which investigated 305 patients with a self-reported physically demanding job attending a rheumatology outpatient clinic with acute LBP and reported a high-risk FAB-W score (>20) in 72.8% of patients [20]. This diference could be due to a lower cut-of (>20) for high-risk FAB-W score, and inclusion of subjects with acute LBP with a physically demanding job in their study [20]. Investigators have reported a greater signifcance and reliability of FAB-W score to predict self-reported disability and early treatment outcomes in patients with LBP vis-à-vis FAB-P score [17, 19]. Our fndings indicate that a greater percentage of patients with spine pain, when derived from a mixed population attending a rehabilitation outpatient clinic, with both acute and chronic spine pain, may have high-risk FAB-P score when compared to FAB-W score. One explanation for this could be that our study population had fewer subjects with chronic spine pain or had a physically demanding job which could have reduced the percentage of patients with a high-risk FAB-W score since both duration of symptoms and work and non-work activities may afect FAB scores [17].

For kinesiophobia, 36% of patients had a medium to highrisk TSK score, indicating less prevalence of fear of movement and recurrence of injury among our patients with spine pain. This fnding was similar to the study which reported a high-risk TSK score in 29% of nursing personnel with LBP [21]. Furthermore, the mean TSK score in our study population was lower than TSK scores reported for subjects in LBP [22]. Kinesiophobia is more prevalent in older, less active subjects with higher pain levels [23]. This could explain the lower TSK scores and lower prevalence of high-risk TSK score among subjects in the current study where the mean age was 41.2 years, and 80% of patients had an NPRS score of≤7. The medium to high-risk SBT score was present in 54% of patients in the current study. This was higher than the medium to high-risk SBT score previously reported for patients with spine pain. A previous study on 496 subjects attending a chiropractic outpatient clinic for spine pain, reported a medium to high-risk SBT score in 21% of patients [24]. However, another study similarly reported a high-risk SBT score in 49.2% of patients in a study of 600 patients who visited the emergency department for acute non-specifc LBP [25].

Subgroup analysis in the current study revealed that a greater percentage of patients with NPRS score>7 had high-risk FAB-W and FAB-P scores and medium to highrisk SBT score whereas a greater percentage of patients with severe, crippled, or bed-ridden disability had high-risk FAB-W and FAB-P scores and medium to high-risk TSK and SBT scores. However, we found patient disability as measured by ODI or NDI score to be the only factor signifcantly associated with higher FAB-W, FAB-P, SBT scores whereas none of the studied factors were found to be predictive of the TSK score. This fnding has been confrmed by previous studies which has reported signifcant association between patient disability and FAB-W, FAB-P, SBT scores but weak correlation between kinesiophobia and pain intensity and disability [26, 27].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the frst study in the literature which has analyzed fear-avoidance beliefs, kinesiophobia, and persistent disability risk among Indian patients visiting a rehabilitation clinic for spine pain. However, there are several limitations to this study. First, although we have used standard instruments to measure FAB, kinesiophobia, and persistent disability risk, these were primarily designed for native-English speakers. Hence, cultural and language barriers may have afected patient response, perception and the quality of data collected [28]. However, this factor may not have played a signifcant role in the current study since a physiotherapist assisted patients who were not fuent in the English language to fll the questionnaires at the clinic.

Second, based on the investigator, the cut-of points for medium or high-risk scores for FAB-W, FAB-P, TSK, and SBT is not standard and has shown variability in the litera – ture which could lead to misclassifcation of subjects into low or high-risk score category. However, we have ensured that the cut-ofs chosen in the current study was based on cut-ofs commonly chosen by diferent studies. Third, FABW, FAB-P, TSK, and SBT scores do not measure other important aspects of the psychological profle of the patient such as depression, anxiety, and catastrophizing which may signifcantly afect symptoms and presentation. We wanted to avoid inconvenience and to make data collection less tedi – ous for the patient in our outpatient clinic and hence were selective in the type of psychosocial variable to be collected. Hence, further research is required to comprehensively col – lect and analyse other psychosocial variables in patients with spine pain. Finally, we measured psychological variables in patients before their treatment and did not determine their efect on treatment outcomes. Hence, a well-designed trial needs to be conducted in the Indian population to investigate the efect of psychological variables on rehabilitation treat – ment outcomes.

In conclusion, a majority of Indian patients who sought treatment for their spine pain at a rehabilitation clinic had medium to high-risk FAB-P and SBT scores. The percentage of patients with medium or high-risk FAB-P, FAB-W, and SBT scores were signifcantly higher in patients with NPRS score >7, and the percentage of patients with medium or high-risk with FAB-P, TSK, and SBT scores were signif – cantly higher in patients with severe, crippled or bed-ridden disability. The ODI or NDI score was a signifcant predic – tor for FAB-W, FAB-P, and SBT scores. The prevalence of fear-avoidance beliefs and risk of persistent disability was signifcant among Indian subjects and should be taken into account while planning treatment for their spine pain. Funding No benefts or funds were received in support of this study by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no confict of interest.

Ethics and institutional review board (IRB) approval This study have been approved by an Institutional Ethics Committee and have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Visit our nearest clinic for your first consultation